Miss America Crew

Top row, left to right: Edward Steele, William Myers, Robert Emmick, Frederich Weyerts

Bottom row, left to right: Gerald Glaze, James Lane, Henry Holderbach, George Harris, Howard Thornley, Elmer Tobias

Here is more information related to Howard Thornley and his mission on December 22, 1943, including:

The names of the crew members, supplied by Mark Farina, whose father-in-law, Casimir Paulinski, was a co-pilot in another B-17 that was shot down on that same mission. Through his research, Farina has identified four planes (three B-17s and one B-24) that were shot down on the mission to Osnabruk, Germany. From these four planes, seventeen crew members died (including nine of the 10 of a plane that landed in the sea), and the other 23 were taken prisoner.

The letter from William Oldenburg that he sent with the return of the bible to my dad. He found the bible in a first-aid kit when the plane came down in Ymuiden (also spelled Ijmuiden) and was able to return it seven years later.

A translated article from a December 1977 Dutch magazine, Samen. Author Larry Scholl visited Ymuiden in the 1980s. He found out that William Oldenburg was dead, but he visited with Oldenburg’s widow and told her the story of the bible that her husband had returned. The widow, who remembered the bible, gave Scholl a letter and some gifts to give to Howard. The gifts included souvenirs from Ymuiden and a 1987 magazine article that had been written about the day that a plane came down near their village. This article was translated for the Thornley family by a friend, Tinie Haagsma, in February of 1992 and appears here.

A letter from Howard Thornley to John van der Maas of Amsterdam in response to a request for more information about the mission in which his plane was shot down. A picture of Howard Thornley from an episode of Air Power by Walter Cronkite. Crew of Miss America, B-17, Serial Number: 42-37738 Pilot: 2nd Lieutenant Edward M. Steele, Jr.

91st Bomb Group, 322nd Squadron

Shot down on December 22, 1943 over Holland while returning from a mission over Osnabruk, Germany

Co-Pilot: 2nd Lieutenant William P. Myers

Navigator: 2nd Lieutenant Robert F. Emmick

Bombadier: 2nd Lieutenant Frederich B. Weyerts

Top turret gunner/flight engineer: Staff Sergeant Henry G. Holderbach

Radio Operator: Tech Sergeant George D. Harris

Left waist gunner: Sergeant Howard Thornley

Right waist gunner: Sergeant Elmer E. Tobias

Ball turret gunner: Sergeant Gerald Glaze (killed in action)

Tail gunner: Sergeant James G. Lane

|

Miss America Crew |

In June 2023, I received a message from Ernest Farmer of Spokane, Washington, who came across documents from Henry G. Holderback, the flight engineer. Henry’s letters to home include details of their liberation and their journey back to the United States: Letters from Henry G. Holderback

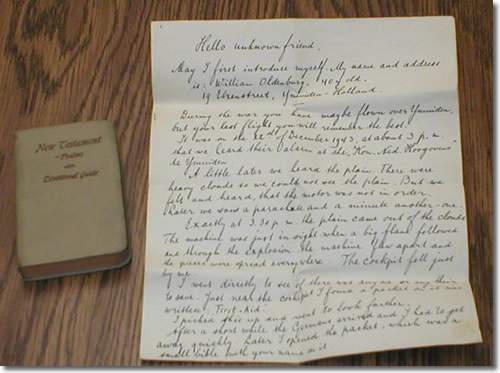

Letter from William Oldenburg that accompanied return of bible, December 31, 1950:

Hello unknown friend,

May I first introduce myself. My name and address is: William Oldenburg, 40 y. old, 19 Ehrenstraat, Ymuiden, Holland.

During the war you have maybe flown over Ymuiden, but your last flight you will remember the best. It was on the 22nd of December 1943, at about 3 p.m. that we heard their alarm at the “Kon. Ned. Hoogovens” in Ymuiden.

A little later we heard the plain [sic]. There were heavy clouds so we could not see the plain. But we felt and heard that the motor was not in order. Later we saw a parachute and a minute another-one.

Exactly at 3.30 p.m. the plain came out of the clouds. The machine was just in sight when a big flame followed and through the explosion the machine flew apart and the pieces were spread everywhere. The cockpit fell just by me.

I went directly to see if there was anyone or anything to save. Just near the cockpit I found a packet on it was written: First-Aid.

I picked this up and went to look farther.

After a short while the Germans arrived and I had to get away quickly. I opened the packet, which was a small bible with your name on it.

Directly I intended after the war to return the Bible to you or your family. I am happy that it is you yourself that I can returned [sic] it to.

Directly after we were free I tried to find out your name and address, and my wife spoke to a Canadian padre. He wrote everything down and said we would hear more about it.

We have never heard anything since. We have tried since quite a few times through different parties without any result.

Now we are determined to send the Bible to you because we think it is the same religious believe [sic] as I am.

We had given up all hope till a country-man of yours came to Ymuiden. This was in summer 1950 and I told him all about it. He wrote down your name again and promised to do something about it.

Now after 7 years boxing-day we received your address. Is not it wonderful! That exactly after seven years we are able to clear this up! I hope that you will write and let me know you receive it savely [sic].

In anticipation I sign myself your

Deutsch friend,

W. Oldenburg

Ehrenstraat 19

Ymuiden,-Oost.

Holland

Ymuiden, 31 Dec. 1950

|

The bible and the letter from William Oldenburg. |

Thirty four Years Ago:

“WE ARE IN A SMART DISTRESS”At the end of the year 1943 it did not look as if the war would be over soon. On the contrary, the war violence seemed to increase in the air above our country.

The harbor mouth with IJmuiden as base for the German Kriegsmarine (German Navy), the Hoogovens (large steel company), the PEN Centrale (power plant), and the Lock Complex were strategically of the utmost importance and therefore regularly attacked from the air. The fearful and penetrating noise of the air alarm and the rattling of the defense artillery started to dominate daily life more and more.

Wednesday, December 22, 1943, it started again; around 12:40 in the afternoon the air alarm was given. Airplane formations coming from the west went land inward at very high altitudes. During their crossing the bombers were fired at in intervals by the Germans situated along the coast.

That day attacks took place on targets in Germany in and around Osnabruck and 579 four-engine planes participated in this raid. Six of the Boeings B-17 were lost during this raid. Three of these planes were noted as lost in the Dutch seas and the crash locations are not known with certainty.

It took a long time before it was quiet again in the sky and the signal “all safe” was given by the sirens. It was then 14:00 hours.

That the attacks did not go very far into Germany became clear from the fact that within half an hour the first planes were coming back, direction England. Again air alarm. The great number of planes followed a different route however to get home; the air alarm this time only lasted till just after 15:00 hours.

But suddenly one could hear the increasing noise of irregularly running airplane engines, and at a lower level. It had to be a plane that was hit, coming from the northeast at an estimated height of 1000 meters above the North Sea Canal. The plane approached the locks and was shot at from all sides. Then suddenly, the clouds were illuminated from the inside out by a sharp red glow. The plane came down in pieces, partially burning, and landing at the Hoogovens site. Many saw the crew, Americans, hanging from their parachutes. Most of them drifted away by the wind in east-northeast direction; the defenseless pilots being shot at from the ground by every type of weapon. It was a miracle that nobody was hit.

Shot Down

An eye witness who was working in the steel laboratory at the time, heard around 15:00 hours a series of gun shots and saw at the same moment from his window a parachute coming down direction Velsen-North: “At the same time there was a tremendous noise, and with the others in the building I immediately fled to the safety of the shelters. Immediately after it became quiet we reappeared and saw that the plane had come down. Very close to the exit of the laboratory a part of the wing with one of the engines had landed; all of it burning.” With a fire hose men tried to extinguish the fire. However, no water was available as the water main was hit and destroyed by part of the plane. A nearby gas container, holding 40,000 cubic meter of gas was miraculously spared. It was a different matter with the Electronics workshop. Here a wing piece with two engines had come through the wall and the roof. The gas tanks in the wings, which still held plenty of fuel, caused the workshop to be on fire. Fortunately the fire brigade had now arrived and could extinguish the fire and prevent further damage.

Another part of the wing landed in the cooling tower between the former buildings 2 and 3 of the Ammonia synthesis of Mekog, while the fourth engine was found near the extinguisher tower of the furnaces. The body of the plane landed on either side of the furnace battery 2. The tail piece was found not far from the former supervisory office.

Crew

How was the crew doing in the meantime? As can be read in the police reports that were kept in Velsen, nine of the ten crew members saved their lives with their parachutes. One crew member was missing; apparently he drowned in the sea close to Wijk aan Zee. Two crew members, possibly one of them being the captain, landed on our industry grounds at the north side of the steel harbor. One of them was wounded because he landed on the edge of a railway car. Employees of the Hoogovens were able to help him and tried to hide the flyer in a space underneath one of the hoisting cranes. However, to no avail, because the German military were there almost immediately. He and another crew member were caught and taken prisoner. The Dutch people were told to leave and they could only watch from a distance. A third flyer did not fare much better. Of this American we know that he was a tall, slender man of about 35 years old. He landed between the apple trees behind a house on the Oude Koningsweg. The lady living there could just offer him a glass of water when he too was arrested by the Germans.

Four of the other crew members were found near Castricum and two near Assendelft. All nine flyers were taken to the Ripperda barracks in Haarlem later that day. From there they were transported to a prisoner of war camp across the border into Germany. Apparently they stayed there until the end of the war.

Wreckage

Right after the signal “All Clear” had sounded—around 15:10 hours—many curious people, German as well as Dutch, approached the wreckage. Especially the painting of a scantily dressed lady on the body of the plane caused a lot of interest and even some discussion on whether she could compete with the paintings by Rubens (as told by a now 90 year old eye witness). And a German officer tried to convince the bystanders that this was a striking example of “The culture of the English.” No one seemed to be much impressed by this statement. The German soldiers now quickly ordered the spectators to leave the “disaster area.”

There was of course much interest in the airplane parts. Pieces of wreckage disappeared, and everybody tried in their own manner—with the necessary risks—to find something of interest. One of the stories goes that one of the steel furnace employees entered the body of the plane and shortly there after reappeared with a flyers outfit. He tried to hide everything under his own clothes, which took too long and a German guard caught him. He was fortunate that he only had to return his find. Afterwards he must have been glad that was all. Many examples existed where people were punished most severely for much lesser offenses.

However, the disappointment must have been great when they had to watch how the German military searched the plane a little later and appeared with items like cigarettes. They knew where to search for supplies. It was a stroke of luck sorely missed by the bystanders. At night there was more opportunity for the “souvenir hunt.” The German keeping watch were lured to the warm kitchens to have a warm beverage and the employees took their chance. In this manner a complete radio set disappeared from the body of the plane. The “electro-engineers” made a lot of noise doing this, though. In order to dislodge the equipment they were using axes. It would have been a lot easier for them if they had just disconnected the plugs and the end of the cables. But you have to know that!

Bobby-traps

Dismantling the radio equipment was not exactly without danger, because explosives were built in. This was done to prevent that the equipment would get into the hands of the enemy. By turning one switch the radio-operator could destroy the equipment on board. Why this was not done will always remain a mystery. But because of this, the “booby-trap” did make itself known again a few years later. One of the engineers experimenting with this particular part, thinking it was a type of radio tube, had a close call. In issue 5, 1947 of the magazine “Samen” the following article appeared under the heading “Dangerous Toys” and summarized that a loud bang sounded and the man was severely wounded. Fortunately it appeared, after the man got to the hospital, that he could keep his left eye, which was thought badly damaged. He did however loose his left index finger.

Chocolate

The rubber that is attached to the front of the wings to prevent ice build up was also a favored article. Much of it found its way to the Dutch families where it was used to repair shoe soles. Aluminum was another material that had been scarce for years and very much wanted for the insulation of steam pipes. What could be found would be used for years after the war. Another item greatly appreciated was an amount of chocolate found by one of the employees near the Walserij-East (one of the buildings at Hoogovens). Apparently the explosion caused it to be tossed out of the plane. The taste was excellent! Everyone agreed on that.

However, the after-taste the “lucky finders” experienced was also long remembered. The story goes that the chocolate eaters had many sleepless nights since there was an anti-sleep ingredient in the chocolate!

During the next weeks the wreckage pieces were loaded onto railway cars near the Mekog buildings. All this happened under the watchful eye of permanent guards. After everything was gone, the last tangible memories of this airplane accident disappeared. Even the names of the crew members who crashed here on that wintery day have remained unknown. Much could have been learned from the log book of the plane that was found by an employee immediately after the accident in the woods near Rooswijk. He remembered very well that one of the last passages read:

“We are in a smart distress . . . ” The book was put in a safe place in one of the drawers of his desk. At least he thought so. Some years after the war, returning from military service back to his department, he discovered that the log book had disappeared.

Information for this article was collected by J. de Groot, employee of the Hoogovens company’s museum. Should there be people that have further information or photos on this subject, please contact Mr. de Groot. Phone: Hoogovens ext. 1022. home (023) 37 84 08

(translated 2/21/92 - T. Haagsma)

Dear Mr. Van der Maas:

On December 22, 1943, we were returning to England after dropping our bombs on Osabruck [sic], Germany. Our plane had been damaged by ME-109’s and FW 190’s. Fire was coming out bullet holes on our right wing. We knew that it was burning the rubberized coating of the wing gas tank and soon would explode. The pilot, after unsuccessful attempts to extinguish the fire, gave us the order to bail out. As we were at 25,000 feet we were fortunate that nine of our crew landed safely. Because of heavy cloud cover, we did not know if we were over land or the ocean. Although we were widely scattered when we bailed out, we were all captured quickly by the Germans.

I was the next to last man to bail out and landed in someone’s back yard of a town. The town was several miles long with all the houses facing the only road. I was taken to the town hall; shortly after, the Germans took me away in a truck, with my other crew members, to Amsterdam.

There we were in solitary confinement for a week. This building was very large with a red brick wall around it.

From there we went to Frankfurt, Germany, where we were interrogated for one or two weeks. From there the officers went to a camp in Germany and the enlisted men to Stalag 17-B in Austria. We were crowded into a small boxcar for four days and nights, without food or water.

After reaching Stalag 17, things got a bit better. We stayed there until late March, 1945, when we went on a forced march. We were liberated in early May, just before the war ended.

Note: Howard Thornley died of a heart attack on March 30, 1987 in Dubrovnik, Yugoslavia, while vacationing with his wife, Phyllis.

Click here to read the experiences of Howard Thornley as a prisoner of war at Stalag 17 during World War II

Note from Stew Thornley (son): When my dad got cable television and a VCR in the 1980s, he watched a lot of shows about World War II and recorded them. During one episode of Air Power by Walter Cronkite, my dad was surprised to see himself (photo above). He thinks it might have been from a beer party after a crew had completed its 25th mission. This would not have been for Memphis Belle, which, although it was also in the 91st Bomb Group, had completed its missions before my dad got to Bassingbourn. The 91st Bomb Group web page has daily reports for the 322nd Squadron. His name appears on four missions, all to German cities: Wesel on November 11; Bremen on November 13, November 26, and December 16. It also notes the December 22 mission to Osnabruk in that Lt. Steel’s [sic] plane did not return. My dad said there were other missions in which they turned back either because of weather or because of heavy assaults from enemy fighters after their fighter escorts had reached their maximum range and had to turn back. I also recall him mentioning a raid on Emden, one that was successful enough that some newspapers referred to Emden as “The City of the Dead.”